The Sites of Phaistos, Aghia Triadha and Gortys

If you are ever in the area of the Messara plain, at a loss as to what to do, you should

be delighted to learn that you have found yourself amidst three of Greece's (if not the

world's) greatest archaeological sites. All extremely important, for different reasons,

the "palace" of Phaistos, and the sites of Aghia Triadha and Gortys (Gortyn and

Gortyna are alternative spellings), are dotted along a line, between the villages of

Tympaki to Aghoii Deka. If you are as foolhardy as I, you can quite easily walk from

one to the others, especially in the cases of Phaistos and Aghia Triadha. I shall not

attempt to give you a "floor plan" to these sites. Most guide books include

these and I would recommend you buy the Rough Guide or the Blue Guide to Crete should you

wish to visit a number of sites, or a bespoke guidebook to these sites, which are

available on the island. The best modern book on the Bronze Age Cretans, is J Lesley

Fitton's imaginatively named 'Minoans'

A few important words on dating. Make sure you take precautions, and never wear red

lipstick until you are entirely sure she'll accept you for it...and...oh yes...

Crete's bronze age history can be divided up in a number of ways. Arthur Evans expertly

dissected periods according to the evidence of vase painting and the strata within which

these and other artefacts were found, into three distinct periods: 'Early Minoan' (EM),

'Middle Minoan' (MM) and 'Late Minoan' (LM). Within each of these time periods, further

subdivisions were necessary. This would seem straightforward at first. EMI is earlier than

EMII for instance. Now for something a little more confusing: To break down these periods

into more distinct timelines, an 'A' or 'B' is added to some of the periods. So, MMIB

comes just before MMII and just after MMIA. O.K. Got that? Well, now for a leap into the

future: 'Late Minoan' (LM), due to its regular new designs can be divided in the same way

as 'Middle Minoan'. but with an extra value- a number - after all of the usual figures, to

qualify its date. So: LMIA is before LMIB, as LMIIIA2 comes after LMIIIA1. Thankfully

there is a clearer system for the novice, and indeed for me:

Neolithic =

c6,000 - 3,000 BC (Neolithic)

Prepalatial =

c3,000-2,000 BC (EM1 to MM 1A)

Protopalatial = c2,000-1700

BC (MM 1B to MM II)

Neopalatial =

c1700-1450 BC * (MMII cont. to LM IB)

There is a period between the one above, and the one below, (c1450 - 1375 BC or LM

II to LM IIIA1), called the 'final palace'

period, which seems to have only affected Knossos, though places - such as Aghia Triadha -

appear to have flourished throughout.

Postpalatial =

c1375-1000BC (LM IIIA2 to LM IIIC)

* Note. Current scientific theory pushes back the the dates around the

Thera eruption, from the archaeologists' preferred 1450 BC to 1550 BC, before arriving

back at a consensus, which only goes to prove that none of these dates are as accurate as

we'd like to believe they are.

Phaistos

Of all the sites on Crete, Phaistos (occ. Festos, Faistos,

Phaestos), in my view, is the most impressive, to the modern day visitor. This may have

much to do with the site's geographic situation; though, for me, it's more likely a matter

of Phaistos' relative calm, compared to Knossos. Originally excavated at the beginning of

the 20th century, by my old mate, Fredrico Halbherr for the Italian School of Archaeology,

(though in the mid 18th century, Captain T.A.B. Spratt, makes mention of it, having

discovered its whereabouts from Strabo's 1st century AD description), between 1900 and 1914 (having

already reconnoitred the site in the 1880s), and then by Doro Levi from 1950 to the mid

1970s. This is a "must visit" site. The cosmetic changes to Knossos, undertaken

by Arthur Evans, early last century, only add to the air of mystique and majesty

surrounding that site's smaller cousin) the central court is around 50 metres long,and 24

metres wide; five metres narrower than that at Knossos, whilst the overall area of the

site, at 8,400 sq. metres, is quite a bit smaller than that at Knossos, 20,000 sq.

metres). Having said that, I'd definitely recommend a visit to Knossos before, rather

than after, visiting Phaistos, as it might help one to make head or tail of Phaistos'

complex make-up. All of the 'palaces' share the common theme of a 'central court'; Zakros'

is far shorter than those at Knossos, Malia and Phaestos, but is, nonetheless there. It

would seem very likely, that the architectural style, was borrowed from the Near East, but

there is one important difference. Wherein the Near East buildings, the central courts

defined the shape of their cities, in Crete, the environs worked outwards, and grew to

whatever size was deemed necessary, which is why these ancient Cretan cities have such a

"sprawling" appearance. The major problem here, is attempting to

extrapolate the evidence that is before your eyes. Remains of far later 'Sub-Minoan' and

Greek sites vie for attention with the "pre-", "proto-" and

"neo-" "palatial" , which can make viewing, somewhat confusing,

especially when compared to the 20th century face-lift which Knossos underwent. The

Italian School did a far better job, in preserving the ambience of this great site.

Certain aspects have been altered, but sympathetically, leaving the infrastructure of the

original to ones imagination. This is a "spirit of place" site, with wonderful

views across the plain of Messara, to greet the visitor. In Greek myth, this was the

home of Radamanthys, legendary brother of King Minos (the other brother, Sarpedon, was a

later interpolated addition by the Greeks; more of the three of them, and other strange

happenings, in a mythological history box, in a later chapter), and, for me, he got the

far better deal as far as choice of accommodation was concerned. Phaistos was settled in

Neolithic times (pre 3,000 BC) and rose to prominence in the next thousand years or so,

eventually becoming one of the five known (Knossos, Malia, Zakros

and Petras; though we can surely add Kydonia - probably hiding beneath modern-day Chania -

to that list, and there may have been more) proto-palatial 'palaces', which were

built in, or around, 2,000 BC. It would seem certain that the devastation of the island's

two primary centres, was caused by island-wide earthquakes, around 300 or so years after

being built. Not easily put-off, the island's architects rebuilt on the same sites,

and created what we see today, which dates back to the early part of the 18th century BC.

A future "history box" will discuss the various forms of writing on Crete, but

one that immediately grabs the imagination, is the 'Phaistos disk (pictured, below), which

was discovered here, in 1908 AD, and dates back to either between1650 BC - 1200 BC or 1908

AD! As I say, more of that conundrum in a later chapter. The largest collection of, as

yet, undecephired protopalatial 'Linear A' tablets were also unearthed at Phaistos, but

very little in the way of works of art; Aghia Triadha (see below), has proven an

exponentially richer source for these, leading to suggestions that as Phaistos waned,

Aghia Triadha grew in influence. Other than parts of the the

central court and the south-east quarter, which have collapsed (a problem of building

upon a hill), Phaistos is superbly preserved. A jaunt over to the west side will reveal

the original palace; this is a jaunt, well worth your while. Curiously, Phaistos was downsized after the

protopalatial period, whilst its "summer palace" down the road, went from

strength to strength. Phaistos, of course, was looted, while Aghia Triadha was not, so

we'll never know what treasures the people of the former, left behind. Thankfully, thieves

weren't greatly interested in pottery or other earthenware objects, and quite a number of

these can be found in the Herakleion Archaeological Museum. As at Knossos, a western

obsession with royalty, has unfortunately scarred the terminology of some of the rooms'

names: The

"Queen's Megaron" and The

"King's Megaron" for instance, are ludicrously dubbed, as we have

little idea what these were used for, and 'Megaron' (great hall), is a term more easily

applied to Mycenaean remains, which these are most certainly not. Later, from Geometric

times (c 8th century BC) Phaistos continued as a city, though in a much down-graded way,

from Mycenaean times, all the way through to its final collapse, at the hands of those

from Gortys, in the 2nd century BC. Hellenistic finds are especially interesting, and

quite a number of post-bronze-age dwellings, can still be seen. Of all the sites on Crete, Phaistos (occ. Festos, Faistos,

Phaestos), in my view, is the most impressive, to the modern day visitor. This may have

much to do with the site's geographic situation; though, for me, it's more likely a matter

of Phaistos' relative calm, compared to Knossos. Originally excavated at the beginning of

the 20th century, by my old mate, Fredrico Halbherr for the Italian School of Archaeology,

(though in the mid 18th century, Captain T.A.B. Spratt, makes mention of it, having

discovered its whereabouts from Strabo's 1st century AD description), between 1900 and 1914 (having

already reconnoitred the site in the 1880s), and then by Doro Levi from 1950 to the mid

1970s. This is a "must visit" site. The cosmetic changes to Knossos, undertaken

by Arthur Evans, early last century, only add to the air of mystique and majesty

surrounding that site's smaller cousin) the central court is around 50 metres long,and 24

metres wide; five metres narrower than that at Knossos, whilst the overall area of the

site, at 8,400 sq. metres, is quite a bit smaller than that at Knossos, 20,000 sq.

metres). Having said that, I'd definitely recommend a visit to Knossos before, rather

than after, visiting Phaistos, as it might help one to make head or tail of Phaistos'

complex make-up. All of the 'palaces' share the common theme of a 'central court'; Zakros'

is far shorter than those at Knossos, Malia and Phaestos, but is, nonetheless there. It

would seem very likely, that the architectural style, was borrowed from the Near East, but

there is one important difference. Wherein the Near East buildings, the central courts

defined the shape of their cities, in Crete, the environs worked outwards, and grew to

whatever size was deemed necessary, which is why these ancient Cretan cities have such a

"sprawling" appearance. The major problem here, is attempting to

extrapolate the evidence that is before your eyes. Remains of far later 'Sub-Minoan' and

Greek sites vie for attention with the "pre-", "proto-" and

"neo-" "palatial" , which can make viewing, somewhat confusing,

especially when compared to the 20th century face-lift which Knossos underwent. The

Italian School did a far better job, in preserving the ambience of this great site.

Certain aspects have been altered, but sympathetically, leaving the infrastructure of the

original to ones imagination. This is a "spirit of place" site, with wonderful

views across the plain of Messara, to greet the visitor. In Greek myth, this was the

home of Radamanthys, legendary brother of King Minos (the other brother, Sarpedon, was a

later interpolated addition by the Greeks; more of the three of them, and other strange

happenings, in a mythological history box, in a later chapter), and, for me, he got the

far better deal as far as choice of accommodation was concerned. Phaistos was settled in

Neolithic times (pre 3,000 BC) and rose to prominence in the next thousand years or so,

eventually becoming one of the five known (Knossos, Malia, Zakros

and Petras; though we can surely add Kydonia - probably hiding beneath modern-day Chania -

to that list, and there may have been more) proto-palatial 'palaces', which were

built in, or around, 2,000 BC. It would seem certain that the devastation of the island's

two primary centres, was caused by island-wide earthquakes, around 300 or so years after

being built. Not easily put-off, the island's architects rebuilt on the same sites,

and created what we see today, which dates back to the early part of the 18th century BC.

A future "history box" will discuss the various forms of writing on Crete, but

one that immediately grabs the imagination, is the 'Phaistos disk (pictured, below), which

was discovered here, in 1908 AD, and dates back to either between1650 BC - 1200 BC or 1908

AD! As I say, more of that conundrum in a later chapter. The largest collection of, as

yet, undecephired protopalatial 'Linear A' tablets were also unearthed at Phaistos, but

very little in the way of works of art; Aghia Triadha (see below), has proven an

exponentially richer source for these, leading to suggestions that as Phaistos waned,

Aghia Triadha grew in influence. Other than parts of the the

central court and the south-east quarter, which have collapsed (a problem of building

upon a hill), Phaistos is superbly preserved. A jaunt over to the west side will reveal

the original palace; this is a jaunt, well worth your while. Curiously, Phaistos was downsized after the

protopalatial period, whilst its "summer palace" down the road, went from

strength to strength. Phaistos, of course, was looted, while Aghia Triadha was not, so

we'll never know what treasures the people of the former, left behind. Thankfully, thieves

weren't greatly interested in pottery or other earthenware objects, and quite a number of

these can be found in the Herakleion Archaeological Museum. As at Knossos, a western

obsession with royalty, has unfortunately scarred the terminology of some of the rooms'

names: The

"Queen's Megaron" and The

"King's Megaron" for instance, are ludicrously dubbed, as we have

little idea what these were used for, and 'Megaron' (great hall), is a term more easily

applied to Mycenaean remains, which these are most certainly not. Later, from Geometric

times (c 8th century BC) Phaistos continued as a city, though in a much down-graded way,

from Mycenaean times, all the way through to its final collapse, at the hands of those

from Gortys, in the 2nd century BC. Hellenistic finds are especially interesting, and

quite a number of post-bronze-age dwellings, can still be seen.

The tourist kiosk sells quite a number of guide books to the site, and if you haven't

already been wise enough to purchase a copy of the wonderful 'Blue Guide to Crete', prior

to your arrival on the island, you could do worse than buy the Ekdotike Athenon guide to

the site.

Aghia Triadha

Despite the fact that Aghia

Triadha (Holy Trinity) is one of the most important archaeological sites in Greece,

there is a fair chance, that you'll be close to alone, should you choose to visit

(especially outside July and August); and choose to visit, you should. Aghia Triadha is,

of course, the modern name for the site; nobody is quite sure what it was called in

'Minoan' times, which is somewhat surprising, given the wealth of material found here (The

'Blue Guide to Crete' suggests that it may have been the 'Da-Wo', found on Linear B

tablets.) Excavated by the Italian School of Archaeology, at about the same time as

Phaistos, work continues to this day at Aghia Triadha. The site is named after a 14th

century (AD) church, and dates back to around the middle of the 16th century BC; i.e. it's

'Neopalatial'. Not that this was the first era that Aghia Triadha was occupied. Far

from it. We know, for instance, that a tholos tomb (Tholos tomb A), found there, uncovered

artefacts dating back to the 3rd millennium BC. It is almost certain that Aghia Triadha

had a market

place with proper shops, rather than temporary stalls, which would make this Europe's

earliest shopping arcade. The sites proximity to Phaistos (3kms west), is curious. What

was its function? A 'Minoan' road, quite clearly links the two sites, so in what way were

they affiliated? It would seem certain that both used Kommos as their port. That old

chestnut, the "summer palace" theory has often been quoted, but Aghia Triadha,

appears to have been too "busy" to have been used merely as a "royal"

recluse. The fact that 'Linear A' tablets were found here, within their own archive

(a gypsum - there's a gypsum quarry a short distance from the site - chest containing 200

or so, clay seals were also found in this room), suggests a far more established site,

than previously thought. As mentioned, above, it would seem possible that during the

Bronze Age, Aghia Triadha grew in importance at the same time as Phaistos' began to wane.

Finds from the 'neopalatial' period, include 146 linear A tablets, compared to a mere four

found at Phaistos, from the same period. O.K., that doesn't prove anything other than

Aghia Triadha went up in flames during this period, as these tablets were rather

ephemeral, and were never 'fired' for posterity, in a kiln, but sun-dried. Any

evidence on clay tablets of 'Linear A' and the later 'Linear B' - found mostly at

Knossos - is as a result of our luck and the ancient Cretans lack thereof, though,

according to the 'Blue Guide to Crete'. other than Linear A appearing on vases, there is

also some "graffiti" found on the walls of a light well, in that script. That

Aghia Triadha was burned is self evident - parts of the site are scarred by evidence of

fire, probably exacerbated by the storage vases containing olive oil - but it continued to

thrive as a community, later than even the mighty Knossos. Aghia Triadha, is shaped

not unlike an 'L', making it extremely easy to get one's bearings, if one is prescient

enough to have brought a map of the site; each of the 'residences' within, had their own

storeroom, which, again, suggests, to me, a community rather than an out of town

residency, though, of course, the whole site may have been used, solely, for the

storekeeping. The Drainage system, is a rather late addition to the site, and is

post-palatial. One of the major problems one encounters visiting any archaeological site,

is the artefacts that piece the history together, are usually in a museum, some way away

from the site itself. Aghia Triadha is no exception. Artefacts such as the 'Aghia Triadha

Sarcophagus' - made of limestone, and beautifully decorated - the 'chieftain's cup' the

'harvester's vase', and the 'boxer vase' (all pictured below) as well as some of the

finest examples of 'Minoan' frescoes (including the famous "cat fresco"), seal

stones, 19 bronze ingots (weighing in at 556 Kgs!), were all discovered here, and can now

be found in the Herakleion archaeological museum, but that shouldn't detract from one's

enjoyment of this fabulous little site. Despite the fact that Aghia

Triadha (Holy Trinity) is one of the most important archaeological sites in Greece,

there is a fair chance, that you'll be close to alone, should you choose to visit

(especially outside July and August); and choose to visit, you should. Aghia Triadha is,

of course, the modern name for the site; nobody is quite sure what it was called in

'Minoan' times, which is somewhat surprising, given the wealth of material found here (The

'Blue Guide to Crete' suggests that it may have been the 'Da-Wo', found on Linear B

tablets.) Excavated by the Italian School of Archaeology, at about the same time as

Phaistos, work continues to this day at Aghia Triadha. The site is named after a 14th

century (AD) church, and dates back to around the middle of the 16th century BC; i.e. it's

'Neopalatial'. Not that this was the first era that Aghia Triadha was occupied. Far

from it. We know, for instance, that a tholos tomb (Tholos tomb A), found there, uncovered

artefacts dating back to the 3rd millennium BC. It is almost certain that Aghia Triadha

had a market

place with proper shops, rather than temporary stalls, which would make this Europe's

earliest shopping arcade. The sites proximity to Phaistos (3kms west), is curious. What

was its function? A 'Minoan' road, quite clearly links the two sites, so in what way were

they affiliated? It would seem certain that both used Kommos as their port. That old

chestnut, the "summer palace" theory has often been quoted, but Aghia Triadha,

appears to have been too "busy" to have been used merely as a "royal"

recluse. The fact that 'Linear A' tablets were found here, within their own archive

(a gypsum - there's a gypsum quarry a short distance from the site - chest containing 200

or so, clay seals were also found in this room), suggests a far more established site,

than previously thought. As mentioned, above, it would seem possible that during the

Bronze Age, Aghia Triadha grew in importance at the same time as Phaistos' began to wane.

Finds from the 'neopalatial' period, include 146 linear A tablets, compared to a mere four

found at Phaistos, from the same period. O.K., that doesn't prove anything other than

Aghia Triadha went up in flames during this period, as these tablets were rather

ephemeral, and were never 'fired' for posterity, in a kiln, but sun-dried. Any

evidence on clay tablets of 'Linear A' and the later 'Linear B' - found mostly at

Knossos - is as a result of our luck and the ancient Cretans lack thereof, though,

according to the 'Blue Guide to Crete'. other than Linear A appearing on vases, there is

also some "graffiti" found on the walls of a light well, in that script. That

Aghia Triadha was burned is self evident - parts of the site are scarred by evidence of

fire, probably exacerbated by the storage vases containing olive oil - but it continued to

thrive as a community, later than even the mighty Knossos. Aghia Triadha, is shaped

not unlike an 'L', making it extremely easy to get one's bearings, if one is prescient

enough to have brought a map of the site; each of the 'residences' within, had their own

storeroom, which, again, suggests, to me, a community rather than an out of town

residency, though, of course, the whole site may have been used, solely, for the

storekeeping. The Drainage system, is a rather late addition to the site, and is

post-palatial. One of the major problems one encounters visiting any archaeological site,

is the artefacts that piece the history together, are usually in a museum, some way away

from the site itself. Aghia Triadha is no exception. Artefacts such as the 'Aghia Triadha

Sarcophagus' - made of limestone, and beautifully decorated - the 'chieftain's cup' the

'harvester's vase', and the 'boxer vase' (all pictured below) as well as some of the

finest examples of 'Minoan' frescoes (including the famous "cat fresco"), seal

stones, 19 bronze ingots (weighing in at 556 Kgs!), were all discovered here, and can now

be found in the Herakleion archaeological museum, but that shouldn't detract from one's

enjoyment of this fabulous little site.

The Aghia Triadha Sarcophagus

The 'Chieftain's Cup'

The 'Harvester's Vase'

The 'Boxer's Vase'

Gortys

There is something utterly compelling about this site. Three times I have visited, and

three times I have found something new to see; or at least a new angle in which to view

the multifarious exhibits, which make Gortys (ancient Gortyn) a kind of al-fresco museum.

Whilst it is certain that Gortys was inhabited during Bronze Age times, its rise to glory

came almost a millennium after the downfall of those most famous of Cretans, the 'Minoans'.

Gortys was a prosperous city from around the middle of the 5th century BC through to the

early 9th century AD, when it was finally destroyed by the Saracens (824AD), never to be

rebuilt. All of those periods are evident here, with Greek, Roman and Byzantine remains in

abundance. It's very easy to get carried away with the age of a site. We all want to see

remains of proto-palatial palaces dating back almost four thousand years, and it's very

easy to ignore places such as Gortys, whilst visiting earlier, inferior sites, scattered

elsewhere on the island. Do not ignore Gortys! What we have here, ranges from an inscribed

5th century "law code", Roman remains of staggering beauty and importance, and a

6th Century AD church, built upon the site where St Paul visited Titos, some 500 years

earlier. Other early Christians were the "Aghoii Deka" (ten saints), who were

martyred in 250 AD by Decius; a village named after these prior-day martyrs, lies just

east of the site. All in all, Gortys makes for a heady combination, and there are

quite a few other interesting features here, allowing one to while away half a day, with a

few other aficionados of Ancient history. If you like your history more aged than

this, you can be sated by the mythology, where Zeus (disguised as a bull) brought Europa,

and conceived a son. His name? Minos. Crete has had some notable visitors in its time -

Napoleon Bonaparte, stayed the night at Ierapetra, for instance - and this site can boast

appearances by such luminaries as St Paul and the Carthaganian general, Hannibal.

According to the renowned and expert archaeologist, Costis Davaras (quite probably my

favourite living archaeologist), the population of Gortys, was around 300,000, at its

pomp. This is an oft quoted figure, but one that, personally, I cannot believe. Yes, it

was a very large and wealthy city; yes people would have gravitated there from all over

the island and beyond. But 300,000? That would equate to over half the current population

of the whole of the island - and twice that of the city of Herakleion (currently Greece's

5th most densely populated city) - all in a city with a diameter, of under 10kms. Not

impossible, I suppose, but, to me, highly unlikely. Some of the

sites are inaccessible to the public at present, but what can be seen is mightily

impressive. The road running from to (or from) Aghoii Deka, nicely dissects the site, with

the three sites listed below, all to its north along with a theatre and the Roman

aqueduct, which carried water here from Zaros, but a trip to the "acropolis of

Gortys" is well worth a visit, enabling one to get a panoramic look at the enormity

of this ancient city. To the south of this road, there is an amphitheatre and a stadium,

the "praetorium" (the seat of the Roman governor who would have overseen the

whole of Crete and Libya too!) and a temple to Pythian Apollo. There are other

places of interest, but these - almost on top of each other - illustrate the great depths

of archaeological importance of sites that make up the wonderful world of Gortys.

Pictures from Gortys:

The Odeum: This is one of five theatres,

amphitheatres and stadia found at Gortys. The odeum, as the name suggests, was Roman, and

was a covered theatral area, used for performances and games. What you see now, dates back to the cusp of the second century AD, and was rebuilt by the emperor Trajan, on a previous site. The Odeum: This is one of five theatres,

amphitheatres and stadia found at Gortys. The odeum, as the name suggests, was Roman, and

was a covered theatral area, used for performances and games. What you see now, dates back to the cusp of the second century AD, and was rebuilt by the emperor Trajan, on a previous site.

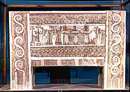

The Basilica of Aghios Titos. This is the first

site you'll see when entering Gortys from the road. Built in the 6th century AD, on an

earlier site where Saint Titos was said to have been martyred, this is one of the earliest

Christian churches anywhere in the world. In the capitals, you'll be able to make out

the monogram inscription to the emperor Justinian. The Basilica of Aghios Titos. This is the first

site you'll see when entering Gortys from the road. Built in the 6th century AD, on an

earlier site where Saint Titos was said to have been martyred, this is one of the earliest

Christian churches anywhere in the world. In the capitals, you'll be able to make out

the monogram inscription to the emperor Justinian.

The Gortys Law Code. Discovered by none other than

Fredrico Halbherr in the 1880s, this is Europe's oldest written law-code; and in fact the

only Ancient Greek one to survive intact. Engraved onto rock in a form of Doric Greek, the

script has 12 columns, with a total of over 600 lines, and is written in

"Boustrephedon" (as the ox ploughs) style (i.e. the script runs alternately

left-to-right, then right-to-left). The Gortyns law dates back to the first quarter of the

5th century BC, though it includes laws which go back a couple of centuries prior to its

writing; these slabs of stone were - and are - very publicly displayed and include all

sorts of fascinating details. The rights of slaves to marry, the rather disturbing

"fine" for rape, which depended on how wealthy the victim was(!) laws on

adoption, divorce property etc., all from a time (early 5th century BC),

contemporaneous with the beginnings of the Athenian Parthenon and the battle of Marathon. The Gortys Law Code. Discovered by none other than

Fredrico Halbherr in the 1880s, this is Europe's oldest written law-code; and in fact the

only Ancient Greek one to survive intact. Engraved onto rock in a form of Doric Greek, the

script has 12 columns, with a total of over 600 lines, and is written in

"Boustrephedon" (as the ox ploughs) style (i.e. the script runs alternately

left-to-right, then right-to-left). The Gortyns law dates back to the first quarter of the

5th century BC, though it includes laws which go back a couple of centuries prior to its

writing; these slabs of stone were - and are - very publicly displayed and include all

sorts of fascinating details. The rights of slaves to marry, the rather disturbing

"fine" for rape, which depended on how wealthy the victim was(!) laws on

adoption, divorce property etc., all from a time (early 5th century BC),

contemporaneous with the beginnings of the Athenian Parthenon and the battle of Marathon.

Aphrodite becomes Venus.

Roman Copy of a Greek original sculpture found at Gortys, and currently residing in the

Herakleion archaeological museum. Aphrodite becomes Venus.

Roman Copy of a Greek original sculpture found at Gortys, and currently residing in the

Herakleion archaeological museum.

Stelios Jackson 2005

|